Climate Change in Himachal Pradesh

INTRODUCTION

Causes of Climate Change

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate change refers to a change of climate that is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and that is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.[1] Human activity, that led to the beginning and recording of climate change, is often attributed to industrialisation and its associated activities. Its inception and continuance are blamed on industrialisation, which continues to be an ongoing process.

Global Warming, a subset of climate change, continues to challenge governments around the world and loop them into the development versus sustainable development debate. To understand how the debate originated, the factors that led to climate change must be understood.

First, a growing population with growing needs. It took 127 years for the world population to double to 2 billion in 1927. After that, the world touched the 3 billion mark in 33 years in 1960, and 4 billion in another 14 years. Cumulatively, it took more time for the world population to touch 2 billion than it did to reach today’s 7.9 billion after 1927. As the population grew at unprecedented levels, the needs of the population – health, infrastructure, food and nutrition – also grew. With industrialisation also came a rise in income levels leading to consumerism and further growth of industries.

Second, industrialisation, before the advent of technology and cleaner fuels, was entirely relying on coal for heat energy and other fossil fuels to run steam engines for mechanical energy. Not only did the indiscriminate usage of fossil fuels lead to depletion of these resources, it also caused extreme pollution. One of the main causes of the Great Smog of London in 1952 was the release of sulphur dioxide from industrial work in urban areas, leading to the death of 12,000 Londoners.

Third, the problem of deforestation is two-fold: trees absorb one of the biggest greenhouse gases, Carbon Dioxide (CO2), and as trees are cut, they are unable to do so; they release CO2 when they are burned as they are made 50% of carbon.[2]

These overarching causes have manifested themselves in different ways. The energy, industry and agriculture sectors now contribute the most to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

As the problem of rise in global temperature came to light, the international community started unifying against climate change.

[1]Unfccc.int/press_factsh_science.pdf

A Framework Convention on Climate Change

Climate law as a concept was noted after the United States President’s Advisory Panel (1965) flagged global warming as a matter of real concern and in 1972, when the first UN Environment Conference took place. Unfortunately, climate change could hardly find itself on the agenda, which ultimately led to the formalisation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In 1987, Montreal Protocol, with an aim to reduce the production and usage of Ozone Depleting Chemicals, became the first and only climate protocol to be ratified by all UN members.[3] After the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, the world community came together for another summit, called the Earth Summit at Rio. The Earth Summit established the UNFCCC, which was then operationalised by the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.[4]

UNFCCC, acknowledging the contribution of developed countries in carbon levels, was based on the concept of a ‘Common, but Differentiated Responsibilities’. Due to these differentiated responsibilities, many developed countries, including the United States refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol again. In 2015, the Kyoto Protocol was replaced with the Paris Agreement that sought to cap the rise in temperature to 2℃ above pre-industrial levels and provide support to developing nations in the process.

Despite the failure of the Kyoto Protocol, the UNFCCC has managed to keep the international community together in the fight against climate change.

Consequences of Climate Change

According to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC[5], global temperature will cross 1.5℃ over pre-industrial levels in the next 20 years, and 2℃ by mid-century. This will lead to changes in sea levels and precipitation patterns, increase in drought and heat waves, and ultimately, a significant rise in natural disasters caused due to climate change.[6]

For Asia and South Asia, heat extremes will increase, and there will be an increase in average and high precipitation. As a result of the changing weather and precipitation patterns, India’s agriculture will also be impacted, including soil quality, fertilizer usage and yield size.

[3]BBC.com/science-environment

ABSTRACT AND DATA METHODOLOGY

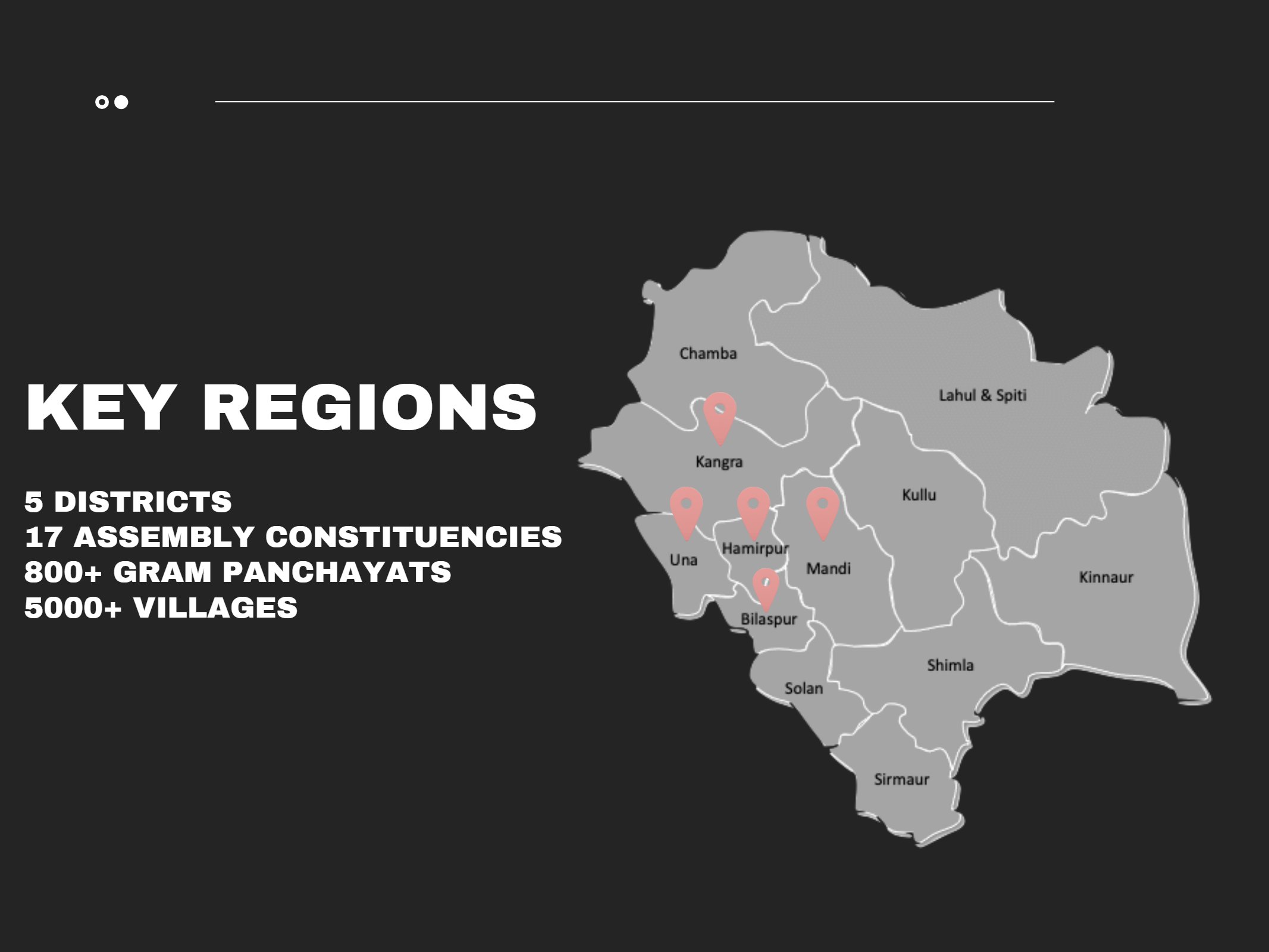

This paper focuses on the impact of climate change on crop yield in the state of Himachal Pradesh in India. Based on the focus on the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report on adaptation to climate change, it also sheds light on some adaptation measures for policymakers (at a local and national level) and farmers/Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) to adopt. The paper analyses the impact of climate change on farmers in Himachal Pradesh from two broad perspectives: agricultural and technical, and socio-economic aspects. The state of Himachal Pradesh was chosen for this paper due to its large agricultural dependency, varied crop production, sensitivity to climate change, geographical placement near the Himalayas, and changing precipitation rates and cycles. The population of Himachal Pradesh stands at 7.5 million as of 2020. 93% of the population is dependent on agriculture and agriculture provides employment to 71% of the people.

This paper uses both primary and secondary data for its insights and recommendations. The findings are based on situational assessment carried out in the Bilaspur and Hamirpur districts of Himachal Pradesh. A positivist and pragmatic approach was followed with primary data collection and quantitative research. This was done through 30 Focused Group Discussions, and telephonic interviews. Focused Group Discussion was chosen for this research because it is a reliable and quick method to collect information from multiple respondents in an efficient and timely manner. Telephonic interview was chosen as a complementary research method in order to cover more abstract aspects of the research.

Two separate questionnaire scripts were prepared for both the approaches respectively, consisting of open questions related to agriculture and climate change. The survey was followed by data processing and tabulation work. The information was collected through a sample of Himachal’s Gram Panchayats. These panchayats were selected based on their geographic locations so as to make the information holistic as well as diverse.

The contacts of farmers were obtained through offices of the local self-governments. Yet, the geographical region covered is limited due to enforcement of COVID-19 related protocols and tough terrain of the state.

An integrated survey was carried out and various estimates related to impact of climate change on agricultural work were included such as cultivable land/resources, yield, profit, market etc. No personal data was collected or presented through the report, and all ethical considerations were followed. All the participants were informed in advance about the purpose of this project. Sector specific survey data was also mapped to findings of Government departments and agencies in the agriculture & Allied sector.

Result of the interview was analyzed manually without using any software because of the diversity of questions. The final assessment was done sector-wise which comprises pan-state statistics and presented through tables in the report.

The towns are located in the Shivalik range of the Outer Himalayas. Both districts are largely dependent on agriculture, with Bilaspur being an agricultural district with more than 70% of the population dependent on agriculture[7]. The major crops grown and studied are Tomato, Cucumber, Bottle Gourd, Round Gourd, Pumpkin, Sugarcane, as well as fisheries and flowers. Himachal Pradesh is the second largest producer and exporter of apples in the country, making it a key stakeholder in the global supply chain of apples. Along with agriculture, Himachal Pradesh is also dependent on animal husbandry.

IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

- Agricultural/Technical Impact

The impact of climate change has been most severe on the primary occupation of the people of Himachal Pradesh – agriculture. Changing weather patterns leading to unpredictable precipitation has created a shadow of doubt in the minds of the farmers of Himachal Pradesh. It is evident that they have already started noticing the impact of climate change on their crops due to dryness and lack of rainfall as one of the main issues.

How agriculture in Himachal Pradesh has been affected can be looked at from two perspectives: water resources and crop yield.

- Water Resources: Since Himachal Pradesh is geographically located in a mountain region, the precipitation is in the form of rainfall and snowfall. The key issue for precipitation in Himachal Pradesh is the growing uncertainty in the patterns. The data available does not provide a clear picture on the trends, and shows random precipitation, leading to uncertainty in agricultural production and crop choices. For example, the post-monsoon rain in September 2018 was 384mm, almost the same as the peak monsoon rain in August 2016; in September 2019, the very next year, it fell to 140mm. Winter rain in December took sharp turns at 42.9mm in 2017, falling to 3.8mm in 2018 and rising to 45.3mm in 2019. This uncertainty and unpredictability of rainfall, in a monsoon-dependent agricultural setting, creates precarious conditions for agriculture.[8]

Through our interactions with farmers on the ground, we found out that 68% of the farmers have realised the impact of low rainfall on their crops, as dryness creates unfavourable conditions for the germination of flowers. 50% of the farmers believe that dependency on rainfall is detrimental for their livelihoods, and requires a switch from this traditional form of irrigation to modern irrigation facilities.

[7]Nabard.org/split-and-merged.pdf

[8]Hydro.imd.gov.in/DistrictRaifall

Similarly, untimely and excess snowfall has created a tough situation for farmers. Farmers in Himachal Pradesh often rely on snowfall as a natural pesticide. It serves a dual purpose: the blanket of snow protects the crop, and as it melts, provides extra nourishment to the soil. It allows for the development of roots, as it did not melt until the germination of the seed. As temperatures increase, the melting process has also increased, leading to the rotting of speeds prior to germination.[9] With unpredictability of snowfall and faster melting of snow, farmers have begun using chemicals (insecticides and pesticides) on their crops more and more, degrading soil and crop quality in the long run. Excessive usage of pesticides also leads to pests becoming resistant to the chemicals, thereby requiring either new chemicals or more application of them. A study[10] indicates that more than 73% of the farmers in three districts – Hamirpur, Bilaspur and Una, use a type of insecticide which is potentially hazardous to human health. In Hamirpur, the percentage of area given pesticide treatment went up from 0.01% in 1996-97 to 8.1% in 2006-07; whereas, in Bilaspur, it went from 0.2% to 2.17%.[11]

The increasing usage of chemicals has led to additional financial burden as cost of production increased and profits went down. Our findings also show that the majority of the farmers continue to struggle due to high costs of pesticides and insecticides (due to growing demand).

- Crop Yield: The crop yield is affected by two major consequences of climate change: precipitation and temperature. A study conducted by the State Centre on Climate Change, under the Government of Himachal Pradesh, shows the impact of climate change (temperature and precipitation) on yield.[12]

The observations from their Yield Model[13] have been placed in the context of Himachal Pradesh, where Kharif crops are rice and cotton, Rabi crop is wheat, and sugarcane is grown all-round the year. The noted mean temperatures and precipitation have also been taken from the study.

- At 22.12°C, marginal temperature increase has a positive impact on all crops (cotton, wheat and sugarcane), but not rice. Considering that the mean temperature through the different seasons is less than 22.12℃, it can be noted that temperature increase does not have a large impact on yield – neither positive nor negative – in the case of Himachal Pradesh.

The opposite is true for rice (convex), which is that any temperature rise until 23.7℃ has a detrimental effect on yield, after which yield improves. In the case of cotton, mean temperature is 15.89℃ during the Kharif season, thereby not impacting yield.

- At 130.45mm precipitation, marginal rise in precipitation levels has a positive effect on all crops (rice, cotton and sugarcane), except for wheat. For sugarcane, the mean precipitation level is low (128.85mm), leading to a smaller yield. Kharif crops – rice and cotton – receive a mean precipitation of 197.39mm, significantly higher and therefore, detrimental. For the Rabi crop, wheat, precipitation is very low at 76.69mm.

- Beyond a certain point, (27.4℃ and 340.5mm for cotton), both temperature and precipitation increase can be detrimental for all crops.

60% of the farmers in our survey also said that their yield has reduced over time due to climate change and has become more erratic and inconsistent.

[9]India.mongabay.com/climate-change-impacts-agriculture-in-the-northern-himalayas

[10]Ijcmas.com/Gaganpreet-Singh-Brar.pdf

[11]Irade.org/Socio-Economic-Vulnerability-of-HimachalPradesh-to-Climate-Change.pdf

[12]Hpccc.gov.in/Agriculture/Climate-Change-and-Crop-Yields-in-India.pdf

[13] ibid, 15.

- Socio-Economic Impact

Due to climate change, crop yield and quality of crop have been seriously affected. Due to crop failure, there is additional weight on the farmers. In 2014, 87.5% of farmer suicides in Himachal Pradesh were due to crop failure.

Himachal Pradesh’s landscape, along with the detrimental effects of climate change, have exposed the people of the state to regular natural disasters, including floods and landslides, among others. These are directly linked with climate change and have caused extreme hardships to the people. Floods have not only threatened their lives, but also their livelihoods by ruining crop produce and damaging property.

NEED FOR ADAPTATION AND TECHNIQUES

The Sixth Assessment of the IPCC lays special emphasis on a two pronged approach to combating the effects of climate change: mitigation and adaptation. While mitigation as a strategy has been talked about in international and domestic law, adaptation has recently come to light. The IPCC Report sheds light on the fact that in a few years, mitigation as a strategy may no longer have any impact on climate change, leaving policymakers with adaptation as the only solution.

For Himachal Pradesh, climate change has manifested itself in the form of erratic temperature and precipitation patterns. There is inconsistency in rainfall and snowfall in both dimensions: region and volume. Hence, adaptation techniques must be focused on combating both the effects of excessive and scant precipitation in agriculture.

Adaptation can be done at both an individual/community level, and at a policy level. Following are some recommendations:

- Individual/Community Level:

- Water Conservation: Installing and utilising proper irrigation techniques such as drip or sprinkler irrigation that are suitable for hilly and uneven surfaces.

- Crop Diversification: It refers to the addition of new crops or cropping patterns to the existing farmland. Crop diversification helps in neutralising the impact of climate change by protecting the natural biodiversity, strengthening the ability of the agro-ecosystem to respond to these stresses, minimizing environmental pollution, reducing the risk of total crop failure, reducing incidence of insect pests, diseases and weed problems and secure food supply opportunities and providing producers with alternative means of generating income.[14]

Intercropping with vegetables that mature every 3 months also provides protection against hailstorms.[15]

- Terrace Farming: As an adaptation measure, terrace farming has two key benefits. First, it enhances soil quality by retaining moisture and protects soil erosion. Second, terrace farming reduces the likelihood of extreme damage from landslides and protects against flooding of downstream regions, as well as of crops planted in the terrace area.

- Crop Coverage: Covering water-resistant crops with sheets or anti-hail nets protect them against excessive rain, cloudbursts, hailstorms and pests.

- Alternatives to Conventional Pesticides and Fertilizers: Pesticides and fertilizers are burdensome for farmers; they increase the cost of production, reduce soil and crop quality, and are extremely hazardous for human consumption. Biopesticides, which are available in the form of bacteria and fungi, act as a natural deterrent for pests and insects. Other plant-derived substances like gluten also act as natural pesticides.[16]

- Chemical fertilizers can be replaced with organic fertilizers in the form of vermicompost, which also acts as a natural soil enhancer.

[14]Researchgate.net/Crop_Diversification_An_Option_for_Climate_Change_Resilience

[15]Dest.hp.gov.in/Trainer-guidebook.pdf

[16]Ift.org/alternatives-to-conventional-pesticides

- Policy Level: While policy level changes can be adopted at an international and national level, the implementation of such policies must be decentralised to the lowest level of governance to ensure accessibility for both rural and urban areas.

- Disaster Preparedness: Disasters are a direct consequence of climate change and cause immediate loss of life and property. Preparing against disasters for protection of both life and crop is imperative. This includes tracing of early signs of disasters and dissemination of timely warnings. There should be close collaboration between the meteorological and agricultural departments at the lowest levels to ensure proper preparation against cloudbursts and other disasters.

- Irrigation Supply: Policymakers should focus on the delivery of irrigation facilities to all areas and ensure their proper utilisation by guaranteeing steady electricity supply.

- Extension and Information Delivery: One of the biggest challenges faced by farmers and collectives is asymmetric information leading to poor understanding of climate change. Proper data collection on climate change and its related trends need to be done to study the adaptation techniques that can be adopted. Additionally, farmers must be trained with these adaptation techniques at the earliest, and all misinformation related to climate change and farming practices must be cleared. For example, despite knowing and understanding the harmful effects of pesticides, farmers continue to use them since they do not have knowledge or access to the alternatives. Information delivery can be done through mass communication platforms such as radio and grassroots training programmes.

- Integration of Sustainable Practices with Existent Programmes: Using existing government programmes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) can be utilised to improve sustainability. For example, setting up of irrigation facilities can be introduced as a MGNREGs project, providing employment, and creating infrastructure at the same time. This integration will allow cashing in of established systems for infrastructural development.

- Climate Adaptation Funds: Since India is an agrarian economy, agricultural climate change adaptation funds should be set up at each level of government – national, state, and rural. These funds should be utilised to provide subsidies and incentives for switches to cleaner alternatives like biopesticides, and to fund technological development.

- Risk Transfer: Weather insurance for crops should be made mandatory to protect farmers from the socio-economic impact of climate change.

- Micro-credit for Technology: Micro-credit guarantee to switch to adaptive farming practices, infrastructural development like setting up of terraces, and capital purchases for technology should be provided to farmers.

- Adoption of Technology: One of the major deterrents to adaptation of climate change is the expensive and inaccessible nature of technology. Adoption of climate smart farming technologies like e-tractors should be encouraged through policy measures such as incentives and subsidies.

CONCLUSION

One of the greatest challenges facing humankind in the 21st century is climate change. The climate is changing and will continue to change significantly over the many years, and if not controlled, can lead to a catastrophic end to humankind as we know it. Effects of climate change can already be seen and felt in the form of increased frequency of fatal natural disasters, degradation of land and soil quality, and unpredictable precipitation patterns. While the effects of climate change have been felt in almost every country and continue to impact every section of the population, the repercussions have been more brutal for farmers and the agricultural sector. The entire population of the world relies on agriculture for food subsistence, and any ramifications of climate change on the industry can be detrimental for the entire world population. More specifically, crops have been facing the effects of climate change since the period of industrialisation. Due to changing patterns of precipitation and temperature rise due to global warming, crop yields are reducing. With a growing population comes growing needs of food security, and low crop yields pose an inimical threat to ensuring universal food security and combating poverty. In the mountainous state of Himachal Pradesh, the precipitation levels have been highly erratic, leading to extreme confusions and lack of clarity of crop outcomes and behaviours. Adaptation in such erratic conditions becomes an even greater challenge, as there are no ideal measures. In such a situation, a proper study on climate change and its effects on Himachal Pradesh is extremely important. This paper provides a perspective on how climate change has impacted the crops and lives of the farmers of Himachal Pradesh. It also provides policy recommendations for the different levels of government in India, along with measures that can be adopted by farmers to shield themselves against any further farm. The policy recommendations focus on a collaborative effort across government levels and departments and participation of stakeholders. This approach is based on the foundation principles of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that combating climate change is a collaborative effort.

Press Mention:

Times Of India

Leave a Reply